Branch Rickey

SABR Bio of Branch Rickey

Baseball-Reference minor league page for Branch Rickey

Baseball-Reference major league page for Branch Rickey

Baseball-Reference Bullpen page for Branch Rickey

Hall of Fame page for Branch Rickey

Branch Rickey began his baseball career while attending Ohio Wesleyan University, playing semipro baseball to help earn money to play for school. (He also played professional football during this period.) He started in the minor leagues in 1903. In 1904, the Cincinnati Reds purchased his contract from Dallas, a Class C club in the Texas League. They returned him to Dallas before he appeared in a game when they found out he wouldn't play baseball on Sundays. The White Sox acquired him from Dallas the following year, but sent him on to the St. Louis Browns when they learned that he wouldn't play games on Sunday and that he wouldn't report until after the college baseball season ended. (He was coaching at Allegheny College.) He finally made his major league debut on June 16, 1905 with the Browns. That was his only major league game that year, as he left the team shortly after when his mother became ill. He finished the 1905 season back with Dallas.

In 1906, he was back in St. Louis for his first full year in the majors at age 24. He played in 65 games as a catcher (starting 55 of them) and hit .284 with 3 home runs and a .345 OBP. (Only George Stone (6) and Charlie Hemphill (4) hit more home runs for the Browns that year, so I guess 3 counted as a power hitter in the dead-ball days.) He shared the catching position with Tubby Spencer (.176/.205/.218) and Jack O'Conner (.190/.199/.190). Just looking at the numbers, I'm not sure why he didn't play more. I suspect it was related to not being willing to play on Sundays. The SABR bio mentions that his arm was hurting by the end of the season, so that may also have been part of it. Baseball-Reference credits Rickey with 2.2 WAR that season, fifth best on the club. Despite this, the Browns traded him to the Yankees during the off-season. (Spencer seems to have been the primary catcher the following year, hitting .265/.299/.335 with 1.6 WAR.)

In 1906, Branch spent the full season with the Yankees, but his arm never recovered. On June 28, 1907, the Washington Senators stole 13 straight bases against him; he wasn't even throwing to second by the end of the game. He retired after the 1907 season and returned to school. He graduated law school in 1911 and set up shop in Boise, Idaho. However, his connections with Browns owner Robert Hedges led to a scouting position with the Browns, and in 1913 he finished the season as the manager of the St. Louis Browns, a position he held for two full seasons in 1914 and 1915. The Browns failed to finish over .500 in either of them. Rickey began extensive use of statistics while managing "hiring a young man to sit behind home plate and keep track of how many bases each player made for himself and advanced his teammates" per the SABR bio.

These two seasons (1914 and 1915) were the two years of the Federal League, with the St. Louis Terriers playing as a third major league team in St. Louis. As part of the deal when the Federal League shut down, the Browns were purchased by Phil Ball, the owner of the Terriers. Ball installed Fielder Jones, who managed the Terriers in 1915, as the manager of the Browns and banished Rickey to scouting for the Browns. In the spring of 1917, the Cardinals hired Rickey away from the Browns to be the club president. After a stint with the Army Chemical Corp in 1918, Branch Rickey returned to the Cardinals for the 1919 season, naming himself manager to save money for the club. The Cardinals had modest success at first under Rickey, rising to third place in 1921, but they did not sustain that success on the field. Rickey was fired as manager by club owner Sam Breadon late in the 1925 season. Under Rogers Hornsby the following year, the Cardinals won their first World Championship in the National League. While the club was doing poorly on the field in the early 1920s, Rickey was busy as team president laying the foundation for that Championship.

The National Agreement of 1903 between the American League, National League, and the National Association (the minor leagues) governed player movement between the minors and majors. The major league clubs could keep 25 men on their roster, while a fixed number of reserve players (8 in 1910, 10 later in the decade, and up to 15 in 1921) could be left on minor league clubs while the major league team retained rights. Players with the same minor league club for two consecutive years could be drafted by a major league club for a fee (no more than one player per club per year). Other players could be purchased at fixed costs depending on the level of the club. This agreement remained in place through the 1918 season. The war with the Federal League and World War I put stress on the minor leagues, causing many to fold. The remaining teams felt the National Agreement restricted their abilities to make money selling the players they developed. After the 1918 season, the National Association withdrew from the Agreement. Player drafts ended, and players could be sold to the highest bidder. This was the environment to which Brach Rickey returned for the 1919 season. The Cardinals, stressed for cash even with their new ownership, could not compete with other clubs to sign the best players. In late 1920, following the hiring of Judge Kenesaw Landis, a new agreement was reached with the minor league clubs. As part of this agreement, major league clubs were allowed to own clubs in the minor leagues, but the 40 man roster remained in place. (Prior to this, teams had covertly owned part or all of some clubs, but the practice was not widespread nor systematic.) Branch Rickey immediately pounced.

After the 1919 season, Rickey convinced club owner Sam Breadon (who took 51% ownership in 1919) to move the Cards into Sportsman's Park in 1920 as tenants of the AL Browns and sold Robison Field (formerly New Sportsmans Park, where Chris Von der Ahe moved the club in 1893) for $275,000. (Beaumont High School was built on the site.) The money from the sale was used to pay off the club's debts and purchase controlling shares in two minor league clubs - Fort Smith in the Class D Western Association and Houston in the Class A Texas League - and a 50% interest in Syracuse in the Class AA International League. Rickey's plan was on a larger scale than anything done up to that point. He envisioned a hierarchical system for player development, with teams at all levels. Players would move up the chain, with only the best making it to the majors. In 1922, after Syracuse balked at selling Jim Bottomley to the Cardinals (after the Cardinals had sent him to Syracuse in the first place), they purchased the remaining ownership in that club and their farm system was begun in earnest. In 1926, the system paid its first dividends, as the Cards won their first World Championship since the days of the Browns in the 1880s. The 1926 club featured a lineup dominated by players who came up through the burgeoning system - Jim Bottomley, Chick Hafey, Taylor Douthit, Tommy Thevenow, Les Bell, Ray Blades, Flint Rhem, and Bill Hallahan, to name a few.

As long as the 40 man roster rule theoretically limited the number of players directly controlled by a major league club, most major league clubs did not invest heavily in minor league franchises, as the entire roster of the club would in theory count against their limit. (In practice, clubs found ways around this, such as selling players to the club they owned, and then buying them back as needed.) By the end of the decade, the Cardinals controlled all or part of between 5 and 10 clubs, while the majors as a whole owned or controlled 29 minor league clubs. Judge Landis was opposed to the concept of a farm system, but because teams were allowed to own minor league clubs, he could not do much to prevent it. He did, however, require teams disclose their interest in minor league clubs. He used this information to force teams to release players for various violations. For example, in 1928, he ruled Chuck Klein a free agent from the team in Fort Wayne, Indiana in the Central League. The Cardinals signed Klein as a semipro player and sent him to Fort Wayne, where he hit 26 home runs in 88 games. Right before the Cardinals were going to call him up that summer, Landis ruled that because the Cardinals owned a club in Dayton, OH, in the same league, sending players to Fort Wayne was a violation. They were forced to sell their interests in the Fort Wayne club and give up control of any players they had there. Klein subsequently was signed by the Philadelphia Phillies, where he started his Hall of Fame career for them that same season.

In 1929, the Great Depression hit, again putting financial stress on the minor league clubs. Other clubs, initially wary of investing in the minor leagues, began to recognize the cost savings in owning minor league clubs as a source of new talent. Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert was one of the most vocal owners calling for a change to system, acknowledging that even the Yankees would soon be forced to buy clubs to avoid paying huge amounts of money for players in a bidding war. The minors also needed the infusion of cash that ownership by a major league club could bring. At the winter meetings of 1931, after much discussion, it was decided that teams could own minor league clubs at the Class B, C and D levels without those players counting against the 40 man limit. Branch Rickey's farm system concept was officially legal. The rule was later expanded to all levels.

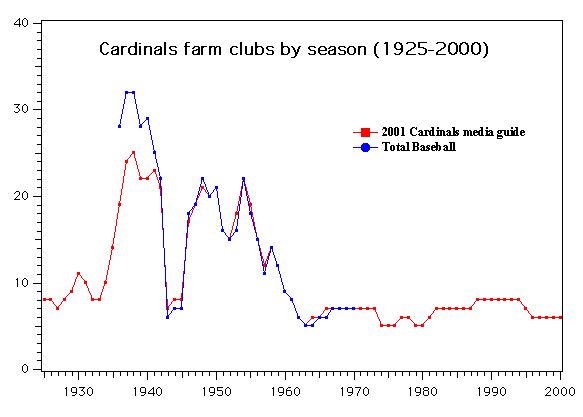

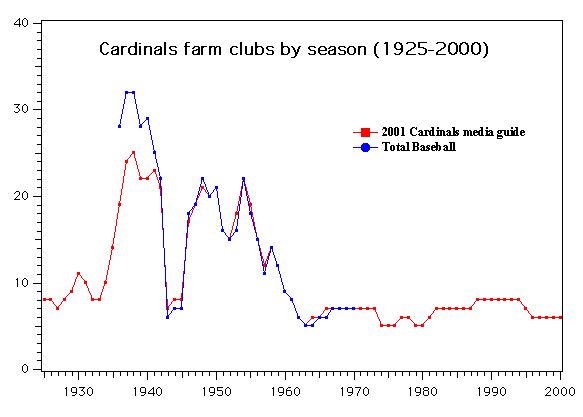

In the 1930s, the Cards system reached its maximum extent, topping out at between 25 and 35 clubs (depending on which sources you believe) late in the decade. To illustrate the extent of the Cardinals operation, consider the case of the Nebraska State League. In 1933, the Cardinals reached an agreement with the league whereby the Cardinals gave $2000 to each of the four teams, and in return, got the rights to acquire up to two players from each club at the end of the season. In 1934, they extended to agreement to get first rights to any players at the end of that season. Commissioner Landis objected to this practice, and in response in 1935 the Cardinals simply purchased 23 of the 52 players in the league. In 1936, they signed two of the clubs (Norfolk and Mitchell) as affiliates, an arrangement they maintained for several more seasons. (See A History of Nebraska Baseball for more information.

In the 1930s, the Cards system reached its maximum extent, topping out at between 25 and 35 clubs (depending on which sources you believe) late in the decade. To illustrate the extent of the Cardinals operation, consider the case of the Nebraska State League. In 1933, the Cardinals reached an agreement with the league whereby the Cardinals gave $2000 to each of the four teams, and in return, got the rights to acquire up to two players from each club at the end of the season. In 1934, they extended to agreement to get first rights to any players at the end of that season. Commissioner Landis objected to this practice, and in response in 1935 the Cardinals simply purchased 23 of the 52 players in the league. In 1936, they signed two of the clubs (Norfolk and Mitchell) as affiliates, an arrangement they maintained for several more seasons. (See A History of Nebraska Baseball for more information.

A similar situation with the Cardinals Cedar Rapids club in 1938 resulted in the Cedar Rapids Decision, one of the last attempts by Judge Landis to stop what he saw as the subjugation of the minor leagues. After an investigation, Landis ruled that the Cardinals and the club in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, with which the Cardinals had a working agreement, were in violation of the policy against owning multiple teams in the same league. Allegedly Cedar Rapids had agreements with multiple clubs in leagues in which the Cardinals also had arrangements. Fines were levied against three clubs - Sacramento (PCL), Cedar Rapids and the club in Springfield, MO. In addition, between 80 and 100 players were granted free agency from across five different leagues (the Three Eye League, the Missouri Arkansas League, the Northern League, the Nebraska State League and the Northeastern Arkansas League). Perhaps the most notable of these were Pete Rieser and Skeeter Webb.

This talent pool fueled the Cards to their first World Series title in this century in 1926 and ensured continued success through the next two decades. The success of the Cardinals farm system may best be illustrated by the 1942 World Championship team, which had only two players who were not developed in the Cardinals farm system. In addition, the Cardinals were able to trade or sell excess talent from their system to improve the club. (Rickey received a percentage of all player sales, which probably contributed in part to the number of sales during this period.)

The size of the farm system shrunk down to less than ten clubs during the war years of 1943-1945. In the latter half of the 40s and well into the 50s, the Cards maintained at least 15 clubs in the minors, continuing the practice that had made the team a dominant club in the National League. (One of the few franchises with as many or more clubs than the Cardinals throughout the 40s and 50s was the Dodgers - then under Branch Rickey - who also had a fair amount of success during that time span.) By 1961, all but one major league club had trimmed back their farm system to under 10 teams (that club, the Dodgers, trimmed down below ten in 1962), and through the 60s most clubs maintained between 5 and 9 farm clubs each year. The Cards reached a low of 5 clubs in 1963, and again from 1974-1976 and 1979-1980. For most of the 1980s and 1990s they maintained seven or eight clubs. They are now holding at eight or nine, including clubs in the Dominican Summer League.

In the 1930s, the Cards system reached its maximum extent, topping out at between 25 and 35 clubs (depending on which sources you believe) late in the decade. To illustrate the extent of the Cardinals operation, consider the case of the Nebraska State League. In 1933, the Cardinals reached an agreement with the league whereby the Cardinals gave $2000 to each of the four teams, and in return, got the rights to acquire up to two players from each club at the end of the season. In 1934, they extended to agreement to get first rights to any players at the end of that season. Commissioner Landis objected to this practice, and in response in 1935 the Cardinals simply purchased 23 of the 52 players in the league. In 1936, they signed two of the clubs (Norfolk and Mitchell) as affiliates, an arrangement they maintained for several more seasons. (See A History of Nebraska Baseball for more information.

In the 1930s, the Cards system reached its maximum extent, topping out at between 25 and 35 clubs (depending on which sources you believe) late in the decade. To illustrate the extent of the Cardinals operation, consider the case of the Nebraska State League. In 1933, the Cardinals reached an agreement with the league whereby the Cardinals gave $2000 to each of the four teams, and in return, got the rights to acquire up to two players from each club at the end of the season. In 1934, they extended to agreement to get first rights to any players at the end of that season. Commissioner Landis objected to this practice, and in response in 1935 the Cardinals simply purchased 23 of the 52 players in the league. In 1936, they signed two of the clubs (Norfolk and Mitchell) as affiliates, an arrangement they maintained for several more seasons. (See A History of Nebraska Baseball for more information.